Last Words: A Lenten Meditation on the Final Sayings of Christ, Week 3ਨਮੂਨਾ

God Is Not Willing That Any Should Perish!

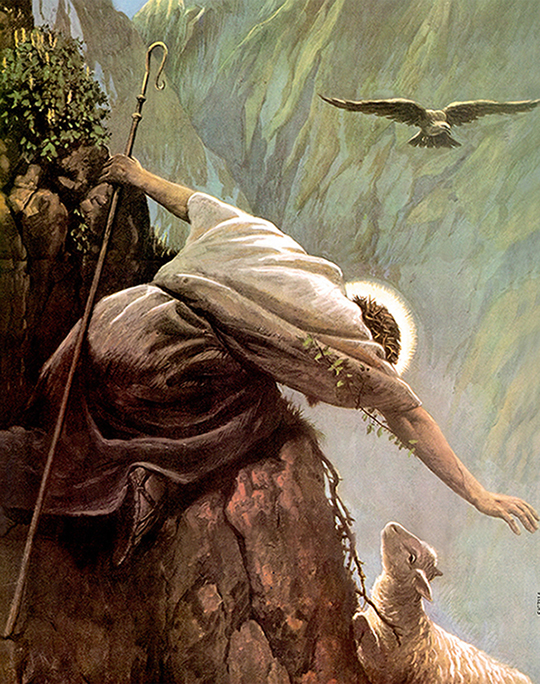

The Parable of the Lost Sheep, Alfred Usher Soord, 1900. Oil on canvas, 275 x 182 cm.

“God So Loved the World” from the album Eternity. Composed by John Stainer. Performed by The National Lutheran Choir.

Poetry:

“The Grammar of Affection”

by Jay Parini

Without syntax there is no immortality,

says my friend,

who has counted beads along a string

and understood that time is

water in a brook

or words in passage,

caravans amid the whitest dunes,

a team of horses in the mountain trace.

There is always movement, muttering,

in flight to wisdom,

which cannot be fixed. The kingdom

comes but gradually,

breaking word by wing or day by dream.

We proceed on insufficient knowledge,

trusting in what comes, in what comes down

in winding corridors,

in clamorous big rooms,

above a gorge on windy cliffs.

In places where discovered sounds make sense,

where subjects run through verbs

to matter in the end, a natural completion

in the holy object of affections

as our sentence circles round again:

This grammar holds us, makes us shine.

WHEN GOD PURSUES WANDERERS

To be truly lost is horrific. It brings dread that can paralyze, freezing our minds in frantic terror. Whether in dark woods at night, or on a snowy remote road with a failed GPS, we can feel helpless. We are the sheep in the painting by Alfred Usher Soord. We look up from a perilous place and see the strong arm of the shepherd—like our Savior—reaching. He came. We didn’t deserve His pursuit. We knew not to stray, yet we did. And now we’re desperate, vulnerable. And there is a divine syntax to all of this. The sentences circle around in “a grammar that holds us,” says poet Jay Parini––words enfolded in action.

In the painting, we can’t see the shepherd’s face. No matter. The sheep can; there’s a quiet recognition in the animal’s look. Body language of this seasoned keeper of sheep is telling. The wide sweep of his right arm is calculated—ready to grip the scruff of that soft woolly neck. The shepherd’s left arm clings to a piece of boulder, and the long staff—normally used to pull sheep to safety—looks like an afterthought. This isn’t about tools. It’s about care, about knowledge of sheep, about shrewd insight into dangerous places and the ways of predators (note the birds of prey approaching).

This shepherd is not willing for this sheep to perish. The painting is based on Jesus’ parable about sheep recounted by the apostle Matthew (18:12-14). It’s interesting that the context of the parable was less about sheep and more about caring for the faith of children. Just as the shepherd left a safe flock to go out after a stray, “In the same way your Father in heaven is not willing that any of these little ones should perish,” Jesus says (18:14).

Peter, who wrote the words in one of our Scriptures today (2 Pet. 3:9) knew about wandering, about the agony of doubt in the face of fear. Peter had, in one of his earliest encounters with the Savior, told Jesus to go away. “I am a sinful man,” he cried out to Jesus (Luke 5:8). But Jesus didn’t go away. He knew Peter’s heart. The exclamation was one of brokenness at the prospect of sitting in a boat with The Messiah. Isaiah felt the same way. “I am ruined!” he said upon seeing God’s glory. “I am a man of unclean lips” (Isa. 6:5).

Everyone knows God is out there, somewhere. Romans 1:19 tells us that what is “known about God is evident” among us all. C.S. Lewis, in The Problem of Pain, says it’s the Numinous—that inner feeling that He is there. That real presence could be fearful to some, a dread. The sheep on that cliff had no idea the shepherd was coming. When he saw a shape up above, perhaps he was afraid momentarily. But the quiet tones of “God so loved the world” in our music today underscores the moment. An embrace is coming.

Prayer:

O God, sometimes I’m so far from you that I can’t find my way back. It’s dark, cold. The voice of the accuser is harsh, screaming in my ears. I feel helpless but whisper a prayer. And I hear your soft but firm footsteps. You come to me with a reminder that you never left. You were closer than my very breath. And when I cried to you, you not only heard but your arms encircled me. Thank you, my Savior, my Shepherd. Thank you for pursuing me. And open my eyes to the lost ones all around me who need someone to go find them as you did me, in rocky unseen places.

Amen

Dr. Michael A. Longinow

Chair, Department of Digital Journalism and Media

Adviser, Print Journalism; Adviser,The Chimes

Co-Adviser, Media Narrative Projects

Department of Digital Journalism and Media

School of Fine Arts and Communication

Biola University

To receive these devotionals in your email inbox, please subscribe via our website at https://ccca.biola.edu/lent/2025. Our website also includes more information about the artwork, music, and poetry selected for each devotional.

ਪਵਿੱਤਰ ਸ਼ਾਸਤਰ

About this Plan

The Lent Project is an initiative of Biola University's Center for Christianity, Culture and the Arts. Each daily devotion includes a portion of Scripture, a devotional, a prayer, a work of visual art or a video, a piece of music, and a poem plus brief commentaries on the artworks and artists. The Seven Last Words of Christ refers to the seven short phrases uttered by Jesus on the cross, as gathered from the four Christian gospels. This devotional project connects word, image, voice and song into daily meditations on these words.

More

Related Plans

Revelation Through Song in 7 Days

Choosing Wisdom

5 Marriage Resolutions You Can Actually Keep This Year

The Christmas Story: God's Greatest Gift

INVITING JESUS INTO the MESS

21 Days of Prayer & Fasting

How to Make Home for the Holidays Happier

New Year, New Me, Same God: Walking With God Into the New Year

Breaking Free From Labels & Finding Identity in Christ