And He Shall Be Called: Advent Devotionals, Week 2Näide

Advent Day 9: High Priest | Prophet

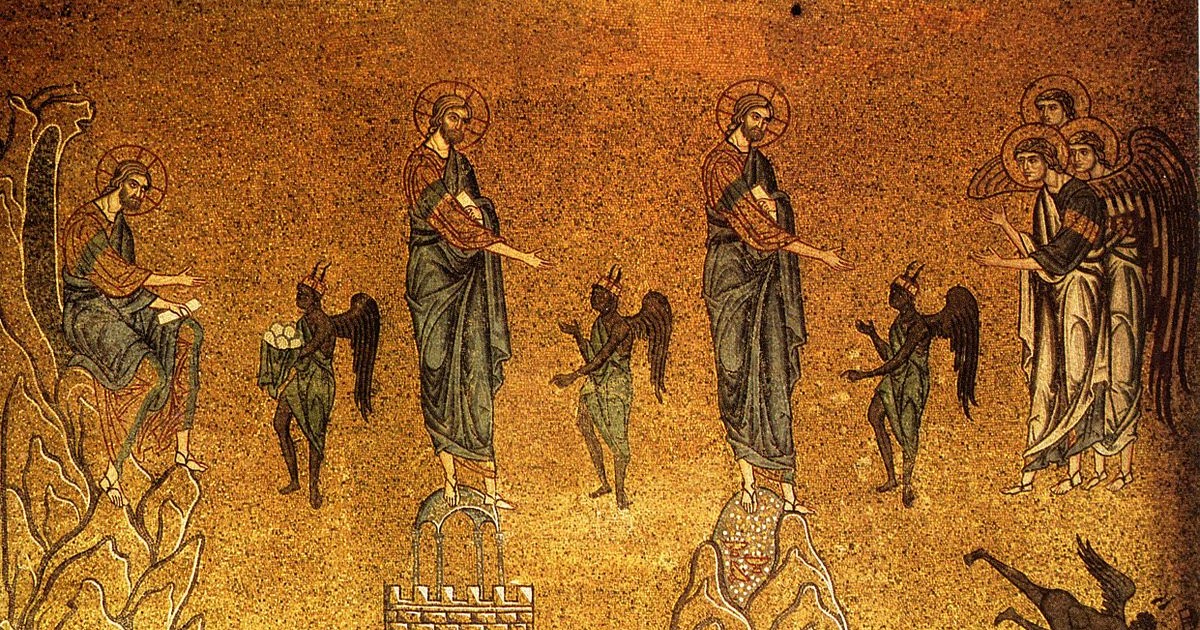

Temptations of Christ, Unknown Artisans, Twelfth Century. Mosaic, Basilica di San Marco, Venice, Italy. Public Domain.

The Great High Priest Enthroned, Anonymous Iconographer.

Holy Monastery Dormition of Theotokos, Parnitha Mount, Greece. Public Domain.

“Before the Throne of God Above” from the album Pages. Performed by Shane & Shane, Composed by Charitie Lees Smith.

Poetry:

“Tempted”

by Eugene Peterson

Still wet behind the ears, he’s Spirit-pushed

up Jordan’s banks into the wilderness.

Angels hover praying ’round his head.

Animals couch against his knees and ankles

intuiting a better master. The Man

in the middle—new Adam in old Eden—

is up against it, matched with the ancient

Adversary. For forty days and nights

he tests the baptismal blessing and proves to his dismay

the Man is made of sterner stuff than Adam:

the Man will choose to be the Son God made him.

Our High Priest

One of the great comforts of our faith is knowing we have a High Priest—Jesus—who feels what we do in today’s turbulent times. The writer of Hebrews states our High Priest is intimately aware of our weaknesses. While some translations use the word “sympathize” (NKJV) or “empathize” (NIV) the message is clear—God enters our pain. Today, we’ll consider the value of human empathy and think about how divine empathy is unique.

Empathy: The Pinnacle of Listening

Emotions are a powerful indicator of how we view the world. The more powerful the emotion the more strongly we feel that something isn’t right or that an injustice has been committed. If our emotions are ignored, resolving differences with a person becomes increasingly unlikely. In light of this, scholars regard empathy as the “pinnacle of listening.” The word empathy comes from two Greek words that mean feeling inside and is defined as the ability to project into a person’s point of view in an attempt to experience that person’s thoughts, feelings, and perspective. Perhaps the most vivid call to empathy is when the writer of Hebrews not only asks us to remember those in prison, but to feel their pain.

Imagine being a persecuted New Testament believer. Upon arriving at a crude jail, you are stripped and whipped. The wounds are left untreated and once put back on, your shirt is soon soaked in blood. Wrists or legs are placed in irons that are only periodically taken off. Meals are unpredictable and when provided often cause dysentery. The problem is, there is nowhere to go to the bathroom. The stench in your cell increases each day. What is most distressing is the cold—especially at night.

In light of these deplorable conditions, it makes sense the writer of Hebrews implores his readers to “remember those in prison” (Heb. 13:3a). This especially takes on significance if the letter was written by Paul who spent 25% of his missionary career in prisons. It’s what the passage says next that relates to our focus on empathy. Think of others “as if you were there yourself. Remember also those being mistreated, as if you felt their pain in your own bodies” (Heb. 13:3b, emphasis mine). Put yourself in their position and then take a close look around. Imagine it’s your pain. How would it affect your emotions and body? How would it increase an urgency to pray?

While empathy may be the pinnacle of listening, is it slowly becoming a lost skill?

Researchers from the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor report that as early as 1980 college students started to show evidence of a dramatic decline in the ability to empathize. Utilizing the Interpersonal Reactivity Index—a questionnaire that asks individuals to respond to empathetic statements—participants rate themselves seventy-five percent less empathetic than students thirty years ago. Why such a decline? While many factors are at play, some researchers suggest our lack of empathy, oddly, may be related to our reading habits. Psychologist Raymond Mar, from York University in Toronto, notes that adults who read less fiction report being less empathetic. Is it possible that fiction encourages us to understand and identify with diverse characters and the emotions they exhibit? Empathy is fostered when we enter another person’s perspective—real or fictional—and ask, “What if?”

When seeking to foster empathy we must be careful not to question the validity of a person’s emotions even if they seem irrational or misguided. Taking a person’s feelings seriously or trying to acknowledge powerful emotions is not the same as condoning the perspective that produced the emotions. Empathy communicates to another person that his or her feelings, beliefs, and perspective matter and you are working to understand them.

When engaging in a conversation with someone who holds a different opinion, it’s beneficial to ask ourselves: Why does this person hold this belief? Such a question helps us not only trace a person’s beliefs to its roots by understanding influential factors such as significant others, experiences, or family, but also to surface and acknowledge the powerful emotions associated with these influencers. Not only will this question yield valuable information about the person you are trying to engage, but it may also dramatically change the communication climate. While still disagreeing, it may foster sympathy. The poet Longfellow writes: “If we could read the secret history of our enemies, we should find in each person’s life sorrow and suffering enough to disarm all hostility.”

Divine Empathy

One of the key doctrines of our faith is that God is omniscient—nothing is beyond his knowledge. To the church in Rome, Paul boldly exclaims, “Oh, how great are God’s riches and wisdom and knowledge!” (11:33). As the passage from Hebrews that started this devotional suggests, this knowledge includes a deep relational understanding of what it means to be human. In referring to Jesus our High Priest, the writer says, he sympathizes with us (Heb. 4:15). New Testament scholar Kenneth Wuest notes the word sympathy “points to a knowledge that has in it a feeling for the other person by reason of a common experience with that person.” Thus, “our Lord’s appreciation of our infirmities is an experiential one [emphasis mine].” This is where Jesus differs from us. To us, empathy is an important moment in the conversation where I attempt to project myself into your situation. You come from a family where your parents divorced when you were young. While mine didn’t, I still try to imagine how that would feel. Even if we both came from homes where parents divorced when we were young, we no doubt didn’t experience it exactly the same.

Here is where Jesus’s brand of empathy is uniquely different. Jesus didn’t have to project himself into or imagine what it’s like to be human. He was human and experienced the full scope of humanity—born to poor parents, being tired, feelings of betrayal by closest friends, unjustly judged, crucified, and dying to name a few. In a shocking passage, Jesus even knows what it’s like to feel God as distant or non-responsive. “My God, my God,” he exclaims from the cross, “why have you forsaken me? (Mt. 27:46). No, Jesus doesn’t have to imagine our pain, he felt it himself.

No doubt we’ve all felt comfort when a friend or family member takes time to empathize with us. The mere fact that they attempt to imagine our pain helps us in our pain. However, such comfort pales in comparison to our High Priest who steps into our hurt and takes it upon himself.

Prayer:

Lord, today let us be quick to enter into the pain of those around us and see life from their perspective. To imagine their pain is ours. Jesus, thank you that you don’t imagine our pain, but feel it in the mystery of your humanity. May it give us confidence to boldly approach your throne of grace as we offer comfort to others and seek it for ourselves.

Amen

Dr. Tim Muehlhoff

Professor of Communication

Co-director of the Winsome Conviction Project

Biola University

For more information about the artwork, music, and poetry selected for this day, please visit our website via the link in our bio.

About this Plan

Biola University's Center for Christianity, Culture & the Arts is pleased to share the annual Advent Project, a daily devotional series celebrating the beauty and meaning of the Advent season through art, music, poetry, prayer, Scripture, and written devotions. The project starts on the first day of Advent and continues through Epiphany. Our goal is to help individuals quiet their hearts and enter into a daily routine of worship and reflection during this meaningful but often hectic season. Our prayer is that the project will help ground you in the unsurpassable beauty, mystery, and miracle of the Word made flesh.

More